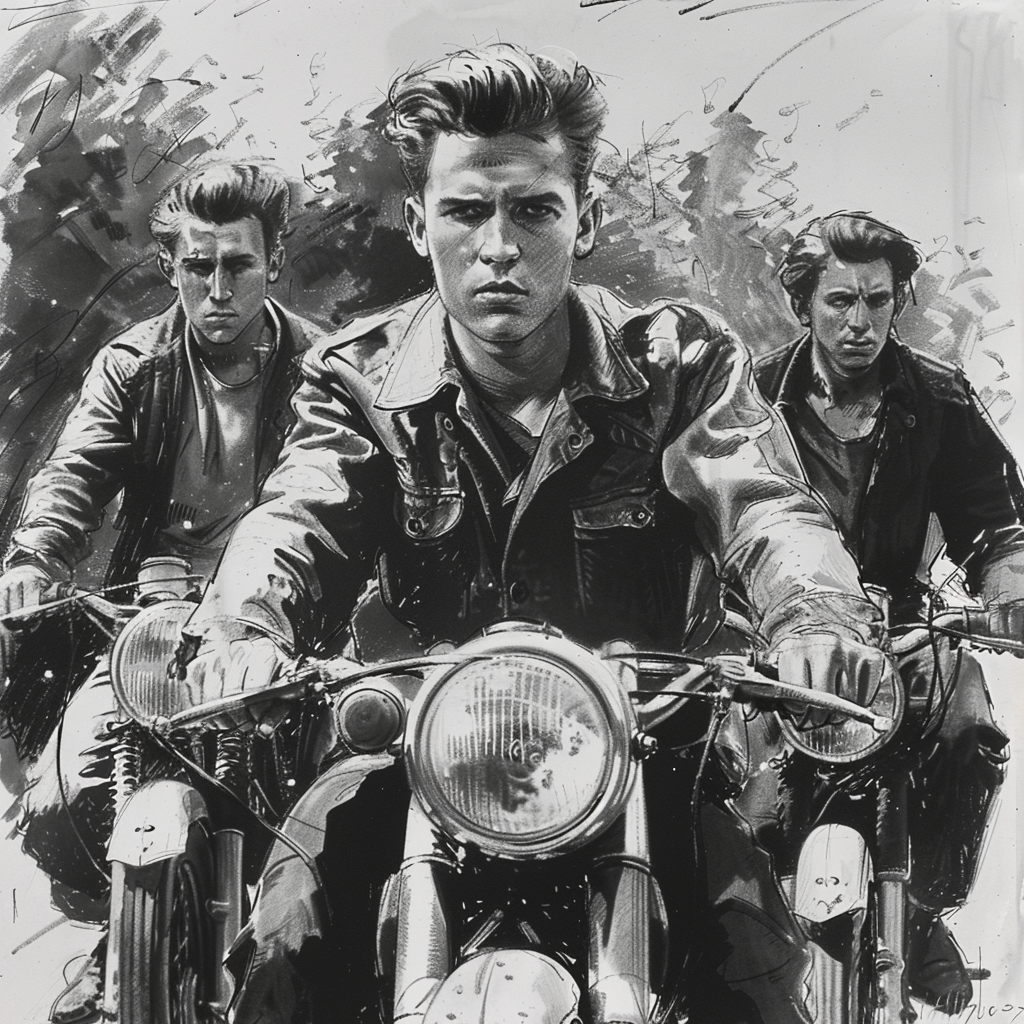

The life of our classic cars was short. New post-war models livened up the streets. Suhl, a town world-famous for its hunting rifle production, had been producing small numbers of the touring AWO since 1950, and more recently a very shapely sporty model.

This post has been moved. Please follow us on Medium to read and/or listen (!) to it in full.

The Bright Side of the Doom, a Prequel to 1984, The 18-Year-Old Who Wrote a Note and Disappeared is now available worldwide in bookstores as a hardcover, paperback, and e-book‼️