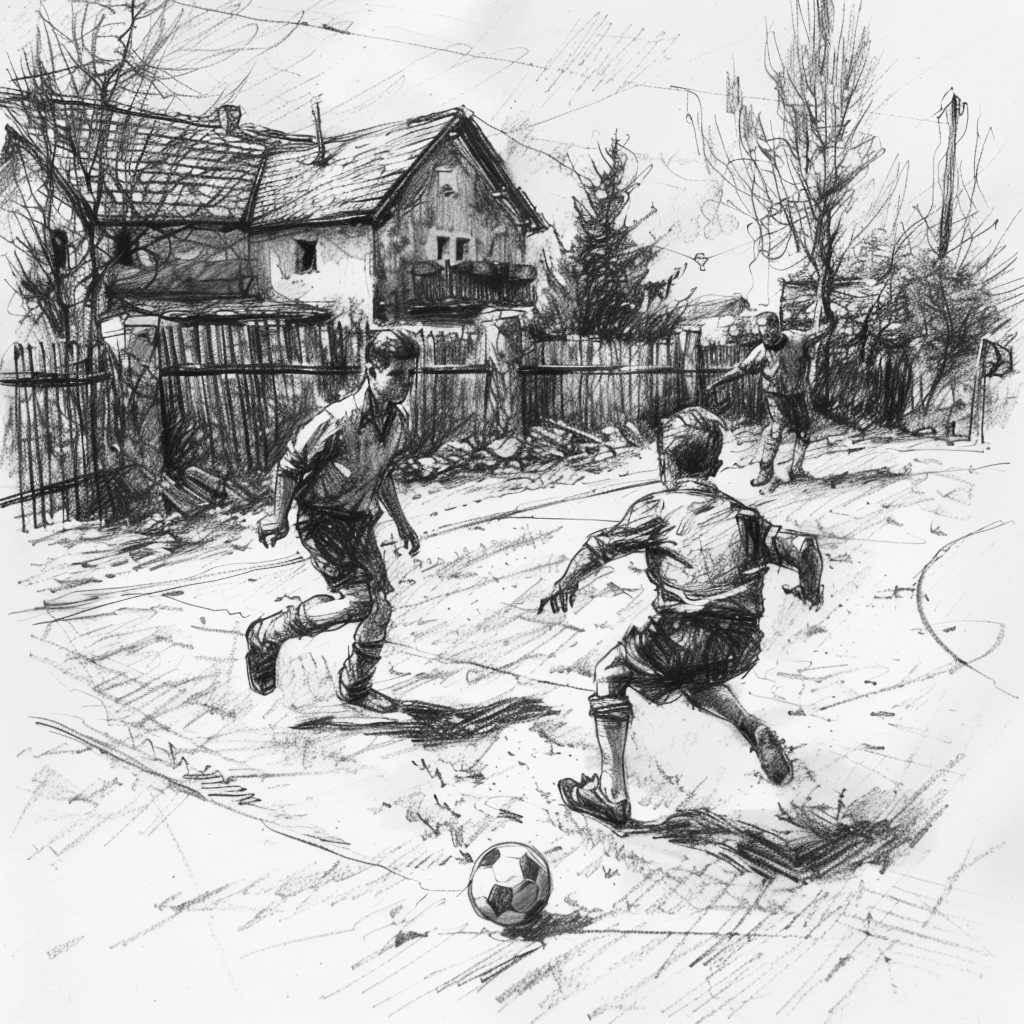

Despite the recommendations and advice from the central assembly, the development of a joyful socialist youth life proved to be extraordinarily difficult. Everything was lacking.

This post has been moved. Please follow us on Medium to read and/or listen (!) to it in full.

The Bright Side of the Doom, a Prequel to 1984, The 18-Year-Old Who Wrote a Note and Disappeared is now available worldwide in bookstores as a hardcover, paperback, and e-book‼️