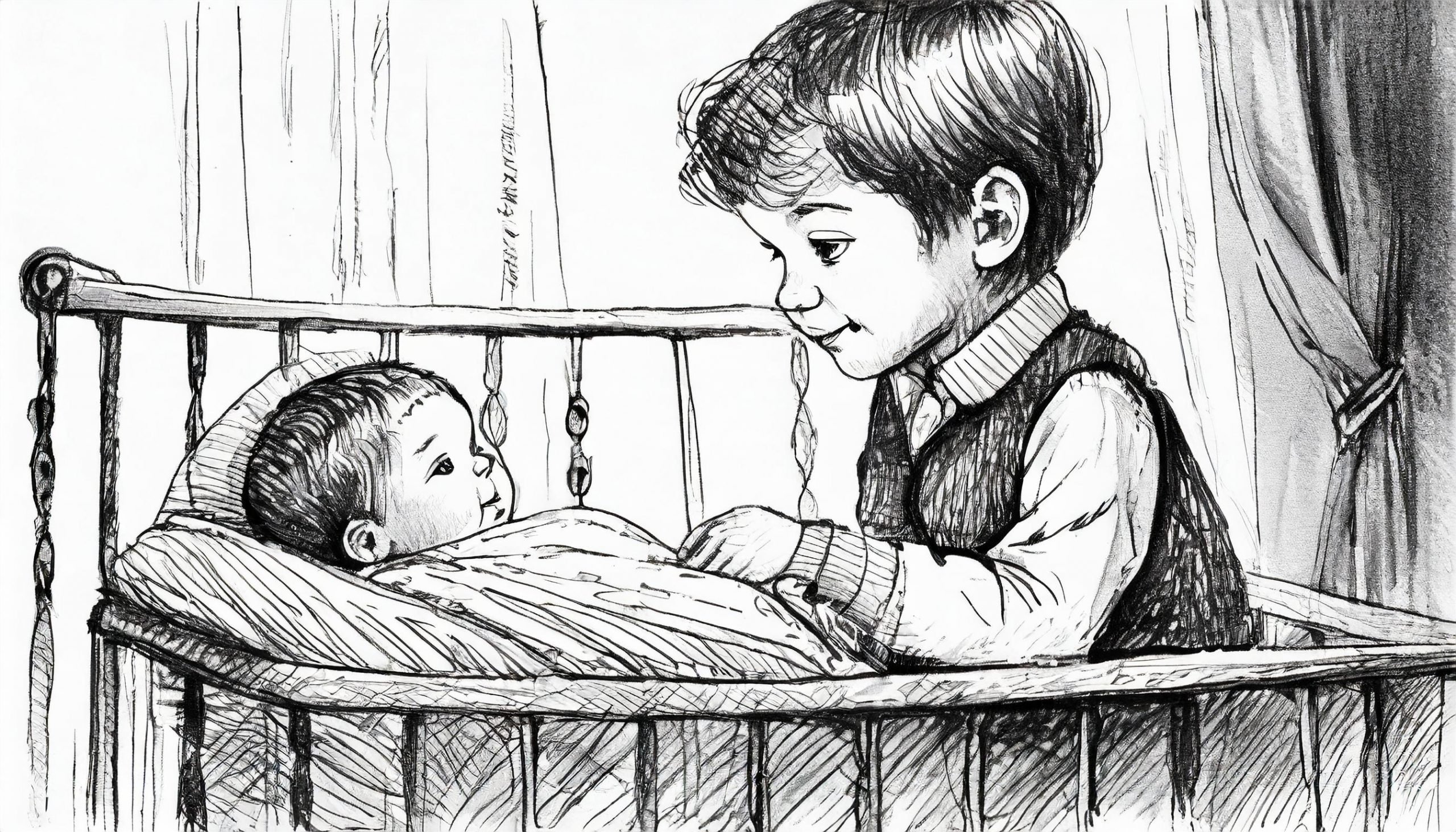

It was in this very parlor that I woke up one morning. My grandmother had woken me up and told me that I now had a little sister. Probably my father had carried me into the room, because in the night with my mother the labor began.

This post has been moved. Please follow us on Medium to read and/or listen (!) to it in full.

The Bright Side of the Doom, a Prequel to 1984, The 18-Year-Old Who Wrote a Note and Disappeared is now available worldwide in bookstores as a hardcover, paperback, and e-book‼️