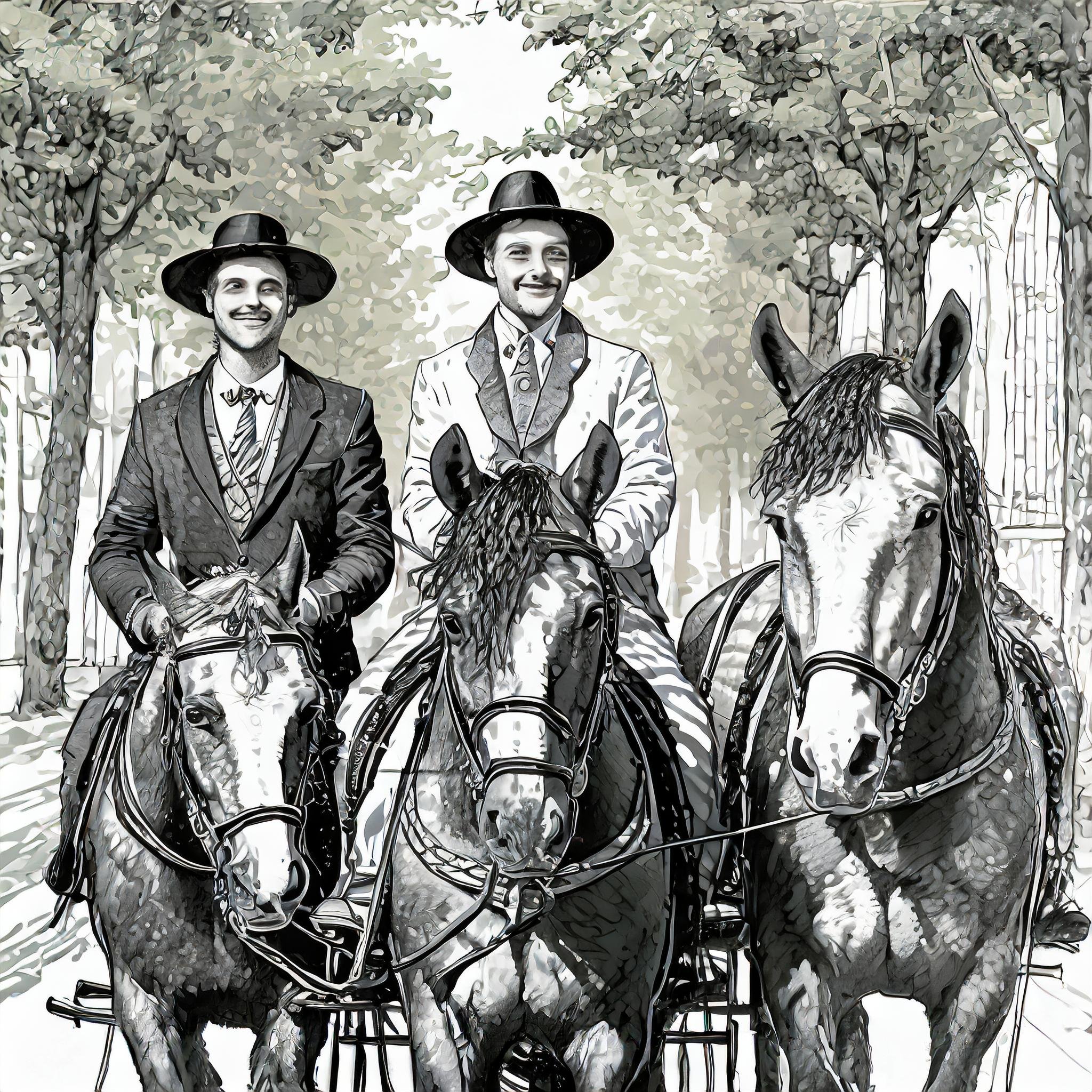

Less noticed, the feast of Pentecost already began a few days earlier. There, the ordered Pentecost May – young birch trees – were distributed by horse-drawn wagon in the village. For this purpose, the Pentecost boys had divided themselves into several groups and drove from house to house.

This post has been moved. Please follow us on Medium to read and/or listen (!) to it in full.

The Bright Side of the Doom, a Prequel to 1984, The 18-Year-Old Who Wrote a Note and Disappeared is now available worldwide in bookstores as a hardcover, paperback, and e-book‼️