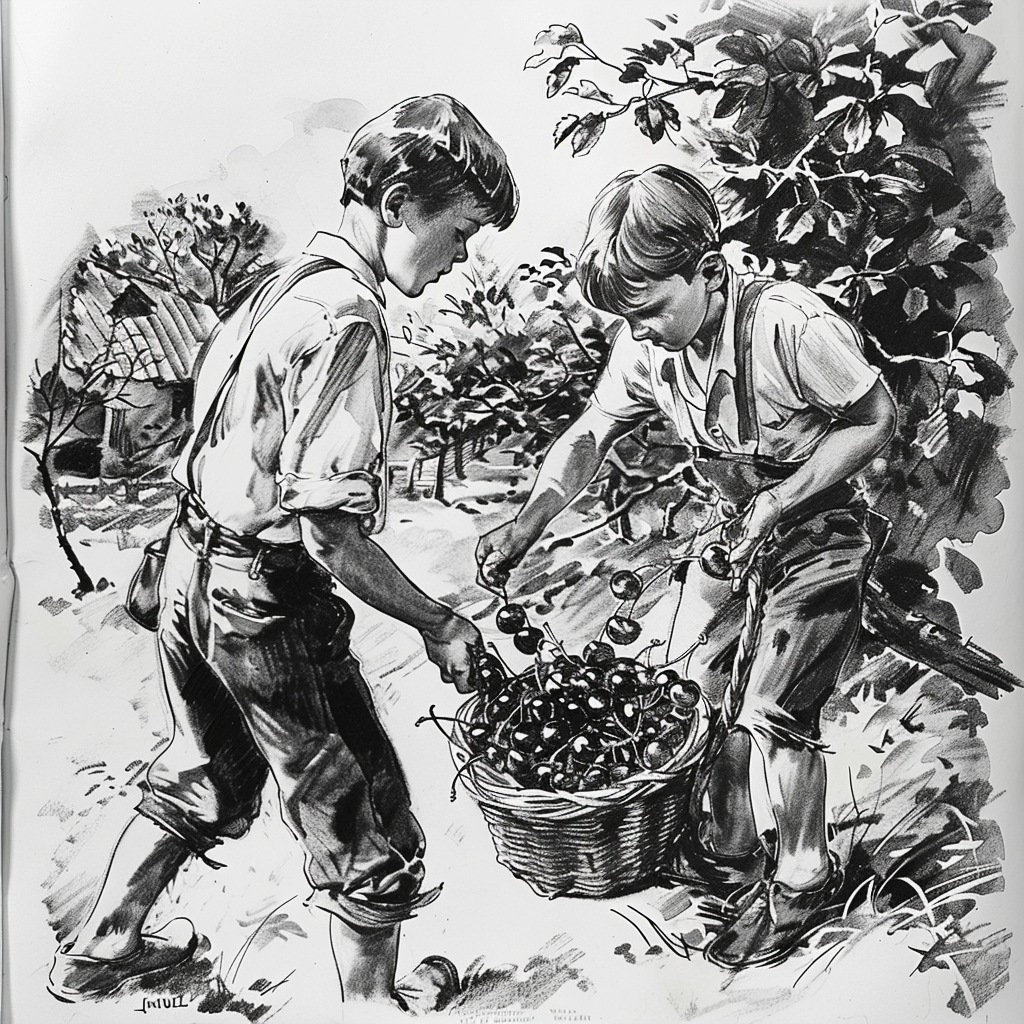

In the first warm days of spring, nature around the village turned into an endless white sea of flowers. It seemed as if fresh snow had fallen overnight. Below the edge of the forest, cherry trees blossomed as far as the eye could see.

This post has been moved. Please follow us on Medium to read and/or listen (!) to it in full.

The Bright Side of the Doom, a Prequel to 1984, The 18-Year-Old Who Wrote a Note and Disappeared is now available worldwide in bookstores as a hardcover, paperback, and e-book‼️