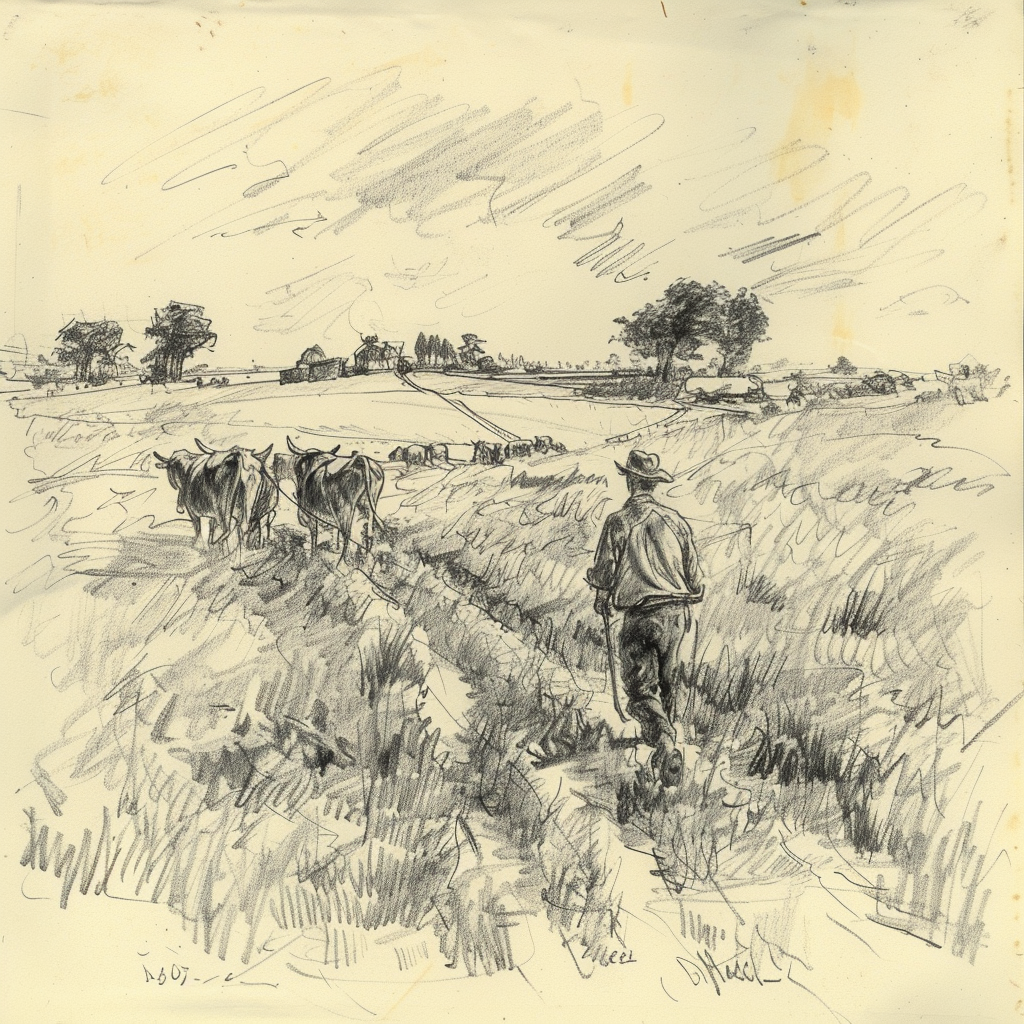

The first post-war harvest had been collected, and the winter potatoes were stored in the cellar. In the fields, the sugar beets waited in long windrows for frosty weather, because when the muddy field paths were frozen, it was easier to transport the beets to the sugar factory.

This post has been moved. Please follow us on Medium to read and/or listen (!) to it in full.

The Bright Side of the Doom, a Prequel to 1984, The 18-Year-Old Who Wrote a Note and Disappeared is now available worldwide in bookstores as a hardcover, paperback, and e-book‼️