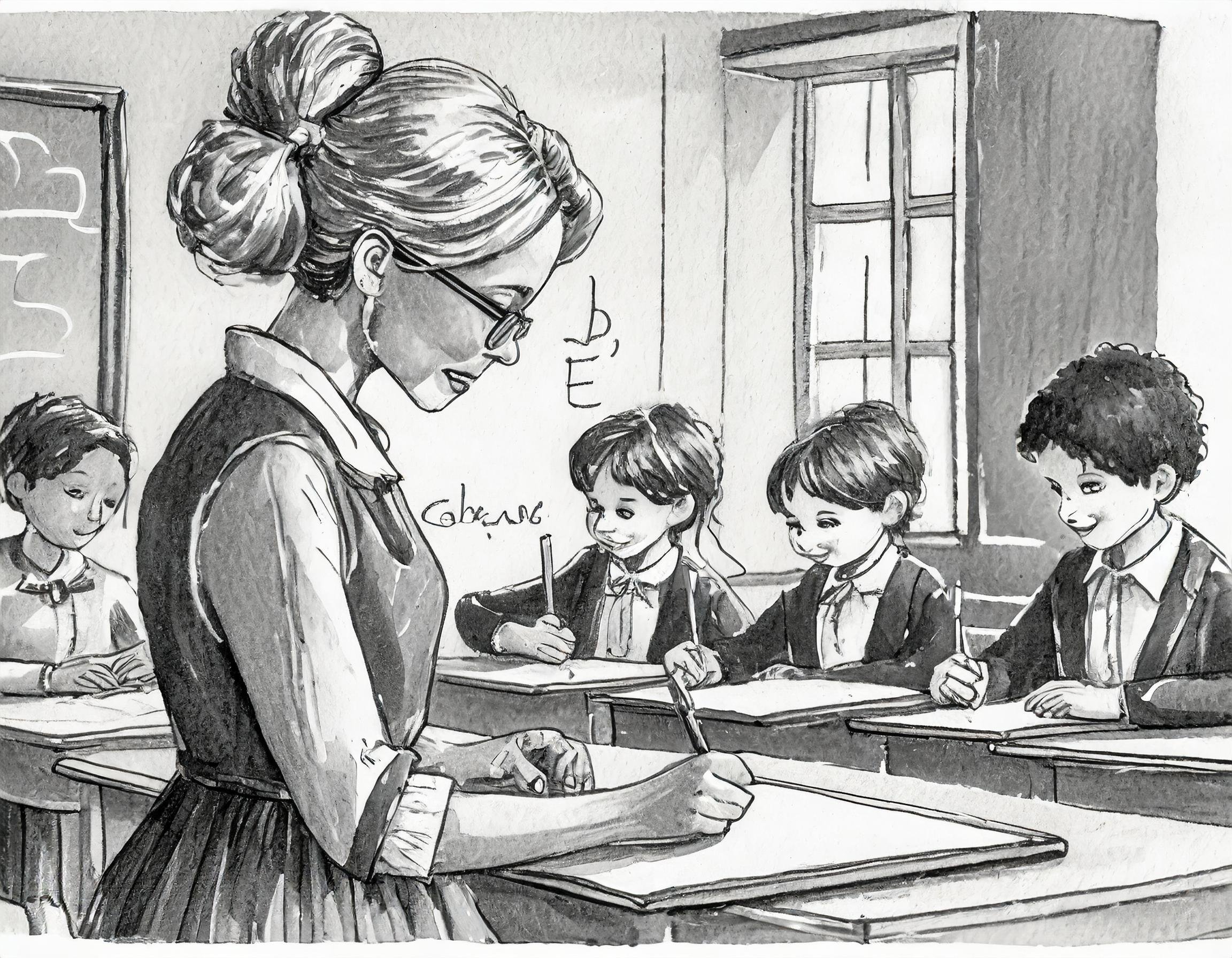

Long before the big move, a new phase of my life had also begun. I started school. In my school bag was a slate board, an arithmetic book, and a reading primer. A damp sponge and a cloth to dry the board dangled from two strings in the satchel.

This post has been moved. Please follow us on Medium to read and/or listen (!) to it in full.

The Bright Side of the Doom, a Prequel to 1984, The 18-Year-Old Who Wrote a Note and Disappeared is now available worldwide in bookstores as a hardcover, paperback, and e-book‼️