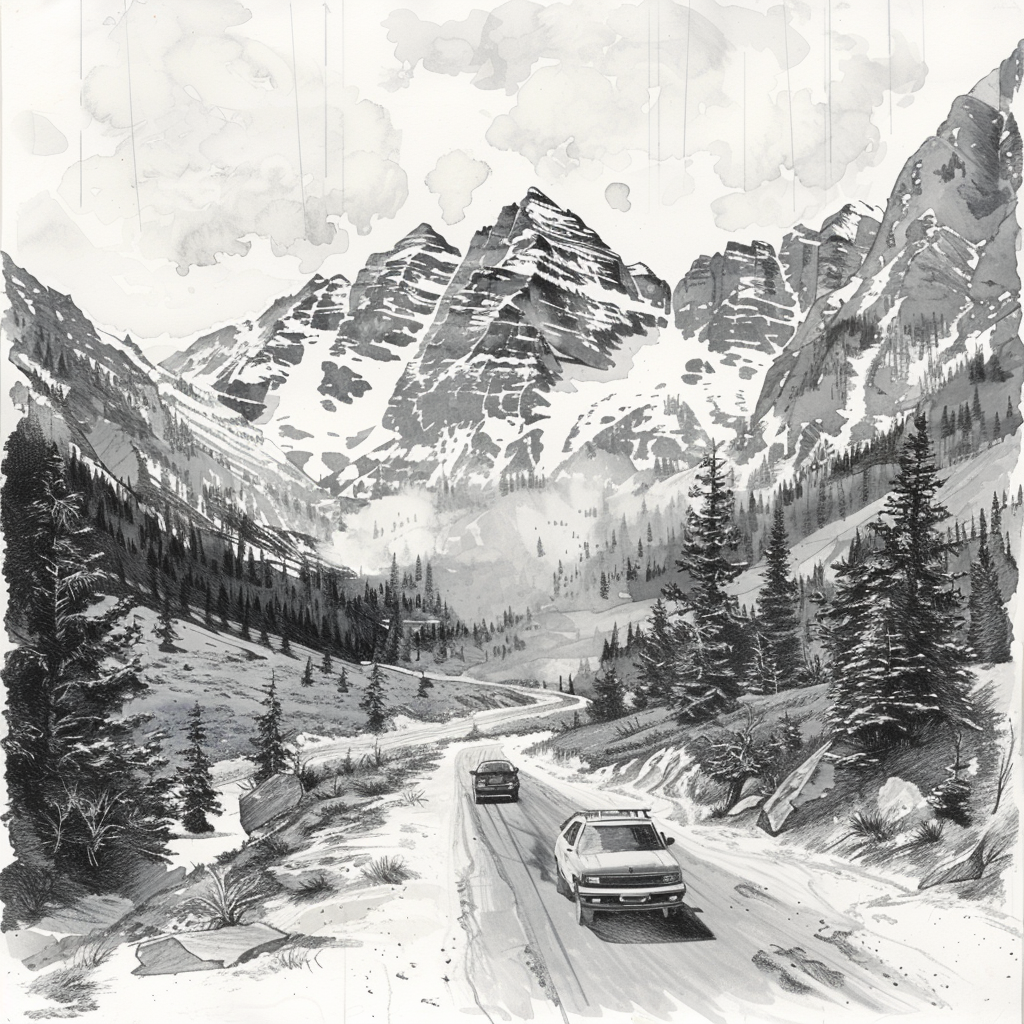

The tent equipment and all travel utensils in the trunk and in the trailer well stowed, the surfboard including mast and boom on the roof rack, so we started with four good mood in the summer of 1985 in the direction of Bulgaria.

This post has been moved. Please follow us on Medium to read and/or listen (!) to it in full.

The Bright Side of the Doom, a Prequel to 1984, The 18-Year-Old Who Wrote a Note and Disappeared is now available worldwide in bookstores as a hardcover, paperback, and e-book‼️